As we continue to mine our vast archive of printed content, we came across this recent classic, from Jacob Negus-Hill, from Issue 39 of Proper. Available in full here.

1980s, Milan, Italy: Regan-era globalisation spread throughout Europe, and the jewels of neoliberalism flooded Italian media with consumerism and hedonism. Italian TV mainlined American sitcoms, cartoons and movies into the veins of the Italian youth. At the height of the ‘80s materialist pushes, fashion found itself of new-found primary importance, and with a host of Italian brands and American imports at their disposal, a small group of Italian youth sought to style themselves in vibrant, sporty and affluence-affirming attire.

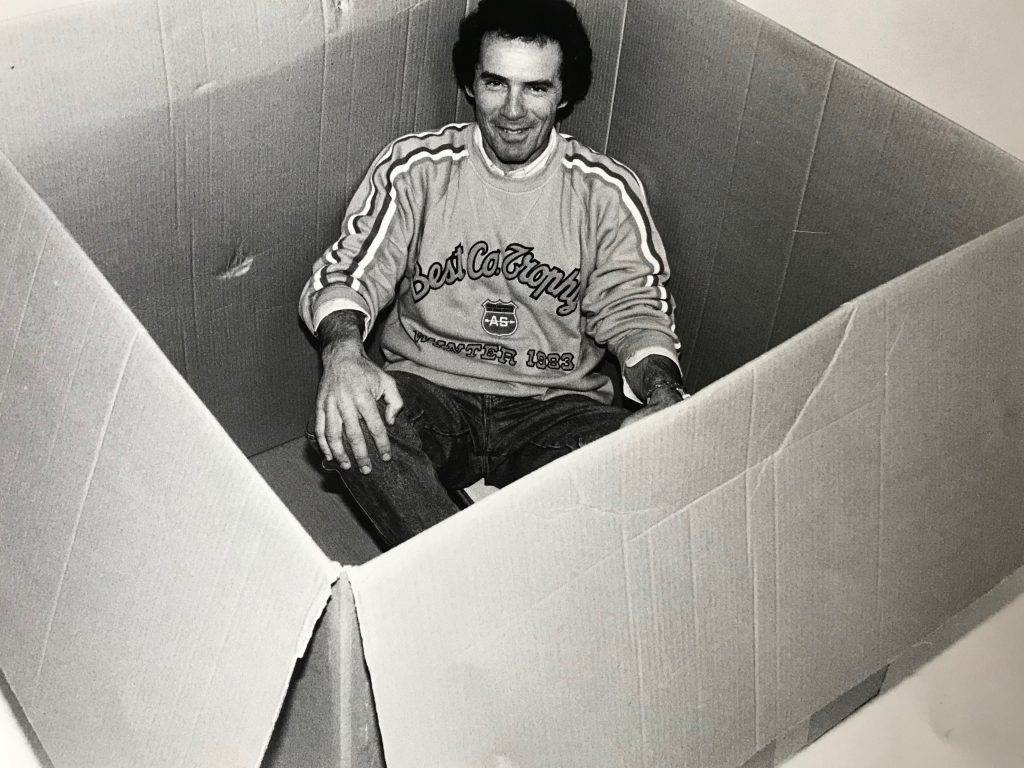

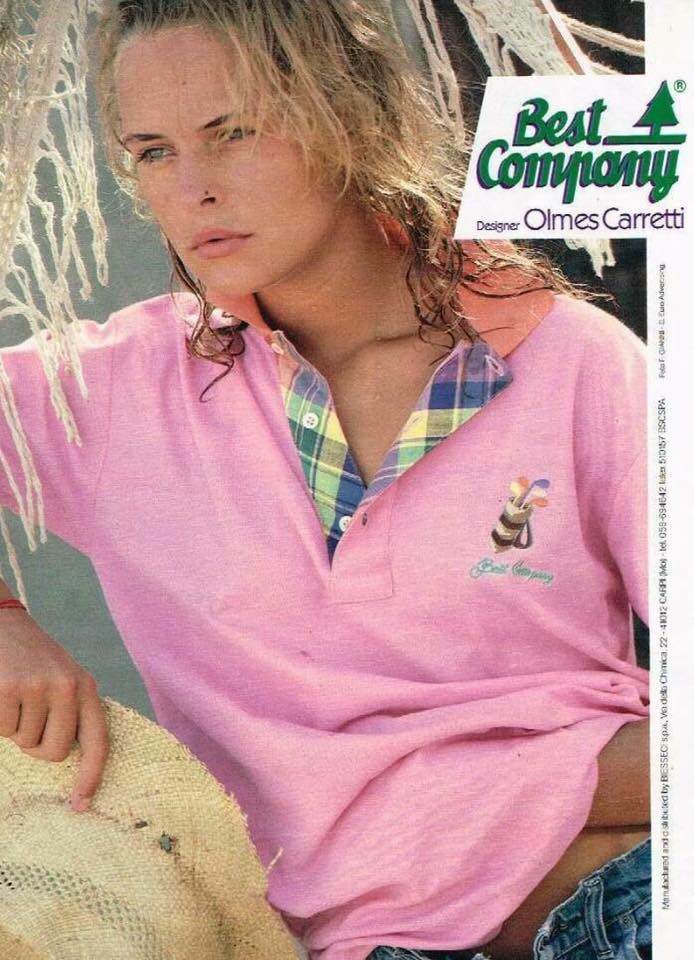

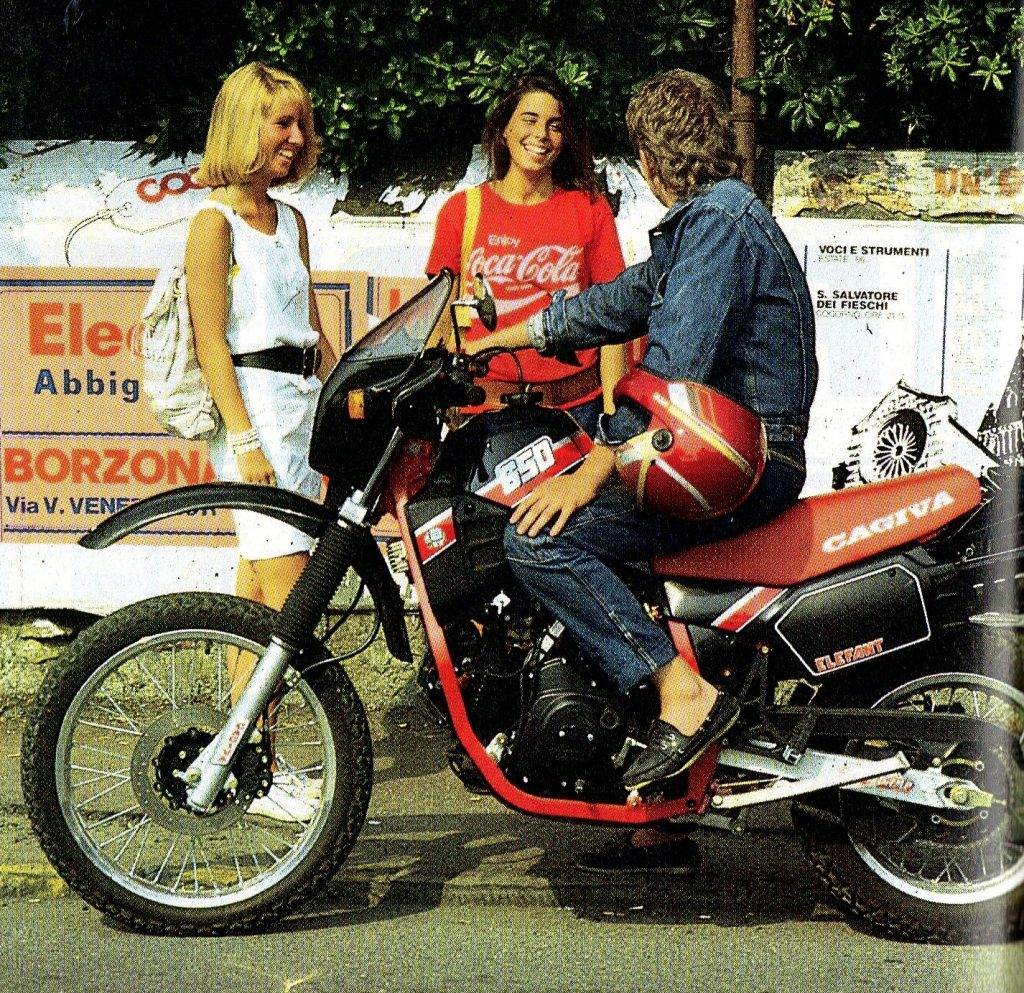

These youths became known as the paninari. Their style was a coalesced form of Americana and homegrown Italian brands, merging turned-up Levi’s 501s, cowboy influences, Timberland boots and deck shoes with Fiorucci, Naf Naf and Stone Island. The paninari flipped a flamboyant switch on a ‘50s greaser by throwing in a load of nautical references and adding a kaleidoscope of colour from Moncler Grenoble jackets and boxy Best Company sweaters, the latter designed by cult-hero Olmes Carretti.

The paninaro trend was a style revolution, but it flowed from a changing political climate. From the late ‘60s until the early ‘80s, Italy was subject to the Years of Lead, a period of political turmoil that destabilised the country. The extreme left and the extreme right fought each other in violent clashes that often resulted in bombing and terrorism. The country watched as radical groups on both sides saddled the political balance.

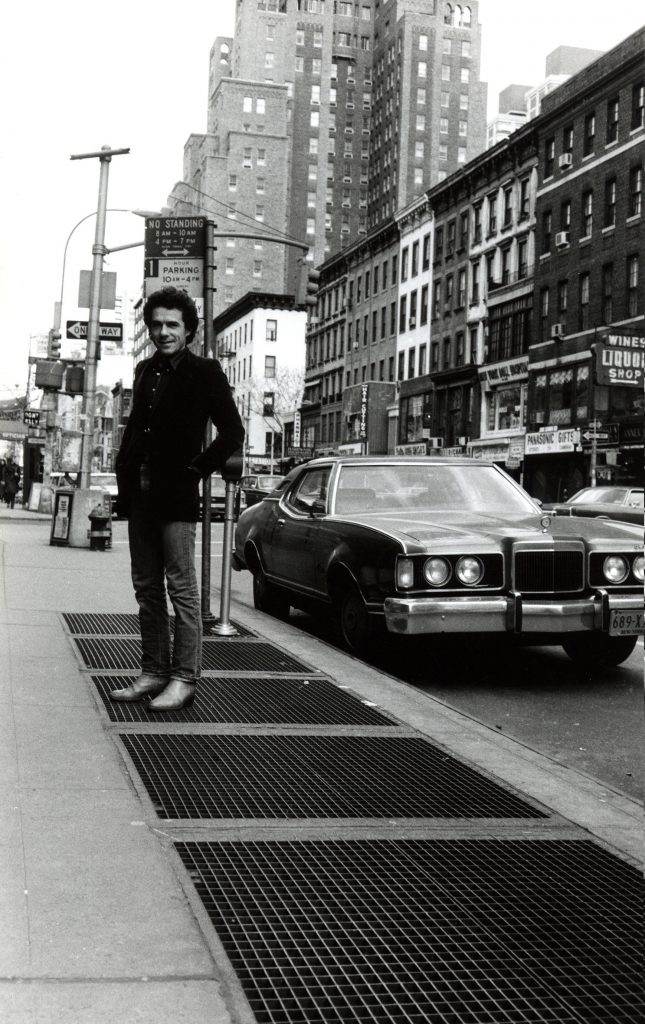

When the Years of Lead calmed down, the youth celebrated their freedom with an apolitical response. They cared little for the politics that the generation before them spilt blood for, and entertained fashion with the gusto of ‘80s hypebeasts. The paninari were a public nuisance. They revved the engines of Italian Cagiva & Gilera trail bikes at now-iconic hangouts, like Milan’s Piazza San Babila and crowded the tables at Al Panino Caffetteria – from where they derive their name. Unlike in the UK, where subcultures mostly developed out of working-class environments and tensions, the paninari were an upper-class affair. Their clothes and bikes were funded by cash held in Coutts accounts and their love of nautical wear informed by weekends on yachts in Sorrento. The paninari were young and rich, but unlike their rich American Ivy League counterparts, they were entirely divorced from sensibility.

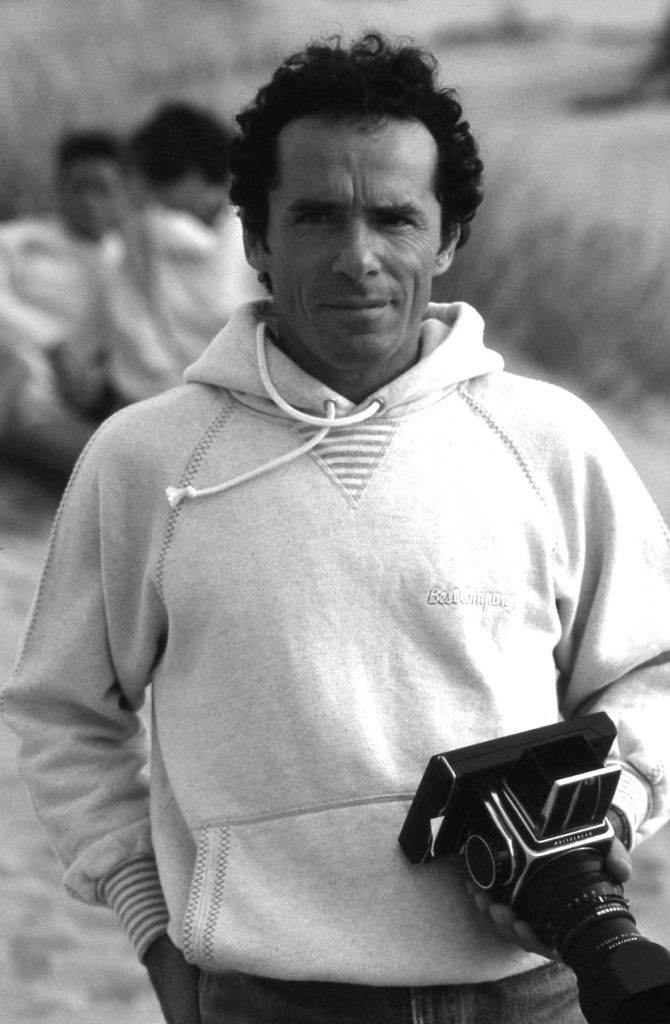

It’s this latter notion that made designers cautious about designing clothes with the paninari in mind. In an interview with Neil Summers, Olmes Carretti describes them as “wild boys,” but as Summers observed, he “became their man of the moment.”

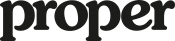

When Carretti founded Best Company in 1982, he was decades older than the paninari. He wasn’t of them, but his designs captured everything that they desired. “At the beginning of the ‘70s,” Caretti writes over email from his house in Reggio Emilia, “I remember visiting Sausalito, near San Francisco. I attended a concert by the Eagles, and then the day after flew to Hong Kong. The people I met while travelling influenced my designs. Best Company was born on that flight out from San Franciso.” Carretti had been to America, he’d seen the influx of sportswear and the shapes of boxy sweaters and brought it all back with him to Italy.

It wasn’t just the shapes and styles that the paninari loved – it was the colours. After Hong Kong, Carretti explored India, Nepal, Bhutan and the Himalayan Plateau, and fell in love with colour and embroidery. “For me, I experienced the feeling of freedom the first time I arrived in India. The nature, the colours, the religions so different from Europe unleashed [in me] a feeling of absolute freedom.”

Best Company’s defining features are the use of colour and embroidery, and these later came to symbolise the entire paninaro movement. Carretti designed his sweatshirts in magenta, fuchsia, sky blue, bright green, deep purples and Naples yellow, inspired by the flowers and colours contained in the patterns he was exposed to on the embroidery which lined the streets of Goa and Kathmandu. The paninari loved colour because it was a stark contrast to the outfits of their fathers – Milanese businessmen in drab suits – and the two groups, Carretti the designer and the paninari consumers, aligned themselves with their new interpretations of freedom.

Before Carretti’s defining style found itself immortalised in the output of Best Company, he started the knitwear brand S.Mortiz in 1976. His contributions to knitwear were appreciated throughout Italy, and he worked with the late, great Elio Fiorucci on a collection between ‘77 and ‘78, just as Fiorucci’s flagship New York store opened. It’s likely that some of the first pieces ever sold at the legendary “Daytime Studio 54” were touched by Carretti’s hands. “Elio has always been a point of reference for me,” declares Carretti, reflecting on the impact of Fiorucci on the fashion world, and it was likely this broader experience that allowed Carretti to begin to change the fashion of Italy.

“In the ’80s, here in Italy, especially in Emilia-Romagna, a style was born called The Sportswear of the Via Emilia.” Brands that fall underneath this heading include Carretti’s Best Company, C.P. Company and Stone Island and the lesser-known design of Filippo Alpi and Guido Pellegrini. “They influence and still continue to be a point of reference in the world today. Between us all there was an excellent relationship and also one of esteem.”

In a 2014 edition of Italy’s Inchiesta di Stile, AKA Style Inquiry, provided by Carretti, the magazine rounds the ripples of the Via Emilia group: “If Massimo Osti has the merit of having brought the down jacket from the mountain in the cities, then Olmes Carretti brought the sweatshirt from sport to metropolis,” showcasing how the brands all functioned together with their own areas of expertise.

“American Colleges were my first inspiration,” says Carretti. It’s hard to pick a piece of ‘80s Best Company up and not find a sports-related motif. His pieces – not just limited to sweatshirts, but an extensive range of gilets, long sleeve polos, long sleeve t-shirts, corduroy trousers and outerwear from varsity jackets to sailing jackets – are typically embroidered with golf, surf, football, ski or sailing references, all delicately decorated with patches and contrasting textures. This proved Best Company’s worth and dedication: “back then, a Benetton sweatshirt cost 20 thousand lire; Best Company cost 140 thousand,” explains Carretti, which was another contributive factor to the paninari’s love for his output. Despite their historical associations, Best Company never once designed for the paninari – they just loved it. “The paninari impulse bought our products. We did not spend one lira in marketing.”

Carretti sold Best Company in 1992 and reinvested the money in a furniture company, an Austrian brand called Haas, which allowed Caretti to explore material and embroidery more closely. He designed carpets, fabrics and other upholstery with a new assortment of colours and textures, in keeping with his traditional designs. A lot of Best Company’s original embroidery revolved around flowers, but these really came to the forefront in the repetitive floral geometry of Haas, where ‘70s psychedelic themes merged with a European sensibility.

In the same year, Carretti began to work with Tibetan wool rugs, bringing his output full circle, and designing items that had an influence on him in his youth. “I began knotting carpets and fabrics with natural fibres in many parts of the world, such as Nepal, Morocco and India.”

It’s easy to associate Carretti’s output with the paninaro subculture, and while their love of his work certainly propelled him to heights and allowed Carretti to design with freedom and clarity, his story transcends them. While the paninari were driving around to the sounds of synth-laden Brit-pop, Carretti was studying the intricacies of budding flowers and contemplating the sound of one-handed claps. As his site’s bio concludes, Carretti’s “contact with Eastern thought enabled him to fathom the true spiritual essence of Man and the gist of the laws that govern every form of life.” The irony of Carretti being a cult hero for a group of young and apolitical hedonists is unprecedented.

Nowadays, at 74, Carretti is still designing clothes, working on the SS23 knitwear collection with Devold Sweaters, a Norwegian brand that might just be enabling Carretti to find a sort of spiritual satisfaction in the pursuit of the perfect knit.