this article was first published in Proper Mag 39

There’s a hypothesis that cats keep us as pets. The premise is that cats weren’t forced into domestic roles like dogs were. Dogs took breaking in – their wills were crushed, their bodies morphed, their roles clearly demarcated. The relationship between dogs and humans is hierarchical. Cats, on the other hand, were astute enough to realise that if they hung around humans and were nice to them, they’d reap rewards. Cats tolerate us – and in turn, we devote ourselves to them. Look at the Ancient Egyptians: cats were revered. They clear out mice from grain stores, kill venomous snakes, scorpions, and provide company. In turn, we mummify them, dedicate gods in their image, and give them their own burial sites. The relationship is clearly reciprocal. If anything, it’s weighed in the favour of cats. But the argument extends further: what of other entities which we allow to flourish in our company? What about mushrooms?

I’m standing in a 3m x 2m zip up grow tent that’s fitted with extractor fans and blue-tinted lighting. The pop-up room is lined with shelves as tall as me that are loaded to the brim with dense, white square blocks. Each block has a different squiggle on it: BKP, CT, WC, and a date. In each of these blocks, there’s a hole cut out the side, and out of some of these holes protrudes a mushroom. The most obvious mushroom is oyster mushroom, and it dominates the room, but there’re countless varieties of mushrooms here, like watercolour oyster, black king pearls, lion’s mane, bear’s head, freckled chestnut. Most of these mushrooms are crossbred with one another to tweak properties like yield, temperature resistance and tolerance for humidity, and they all require slightly different attention.

If you haven’t already made the connection: I’m standing in what is effectively a hydroponic tent browsing cross-breeds of species, except my fingers aren’t green. The smell is pungent, but it’s a mellow and earthy aroma that’s nutty and charming rather than overwhelming. I’m standing in Altrincham’s – and Manchester’s – finest DIY mushroom lab.

Polyspore began during the pandemic. It’s a familiar story: Dylan Pybus & Mike Fothergill found themselves without work and an abundance of time on their hands. They turned their sights towards more exciting prospects: growing mushrooms.

It was a DIY endeavour that took a lot of trial and error, but in about half a year, the boys moved it out of their clandestine bathroom and secured themselves a unit on the top floor of a warehouse – and it’s entirely packed to the brim with mushroom growing equipment and paraphernalia.

After 10 months of operations, Polyspore has got a whiteboard with two columns: quotas they can make and quotas they can’t. The latter column is essentially registered interest, and both columns are full of high profile clients like Where The Light Gets In, The Creameries, Another Hand, Trove and Elnecot. If you want to know which restaurants in the Manchester area really live their commitments to local supply chains, then check their phonebooks for outgoing calls to Polyspore.

Dylan & Mike don’t just grow mushrooms for restaurants, although that is the bulk of their current supply. The two have larger dreams that utilize the many strengths of mushrooms and mycelium. Here, it’s important to note the difference between the two: mushrooms fruit from mycelium. Mycelium is the (often invisible) entity that mushrooms grow from. But its influence shouldn’t be overshadowed. Mycelium grows like a labyrinth of thin tubes underneath extents of land, permeating and interconnecting the domains of soil, trees, algae, plants, animals, even rocks and oceans.

When mycelium reaches a certain stage in its development – an age, a change of temperature, a sudden climatic shock – it will fruit. This is a survival mechanism. The fruit carries and distributes spores that the mycelium needs for reproduction.

In an evolutionary sense, the differences present in the variety of mushrooms are to ensure that they’re picked up and spread in a multitude of ways. The addictive, deep umami smell from a porcini mushroom? That’s to ensure someone or something picks it.

Underneath every football pitch size of organic English pasture, lives a mycelium biomass the size of 15 sheep. Even more shocking is that if you were to strip the entire planet of every single piece of biomass except mycelium, you’d be left with the ghostly outlines of pretty much every single tree, bush, grass, topsoil, rock, and even some human artefacts. Mycelium can grow on, around and in almost everything.

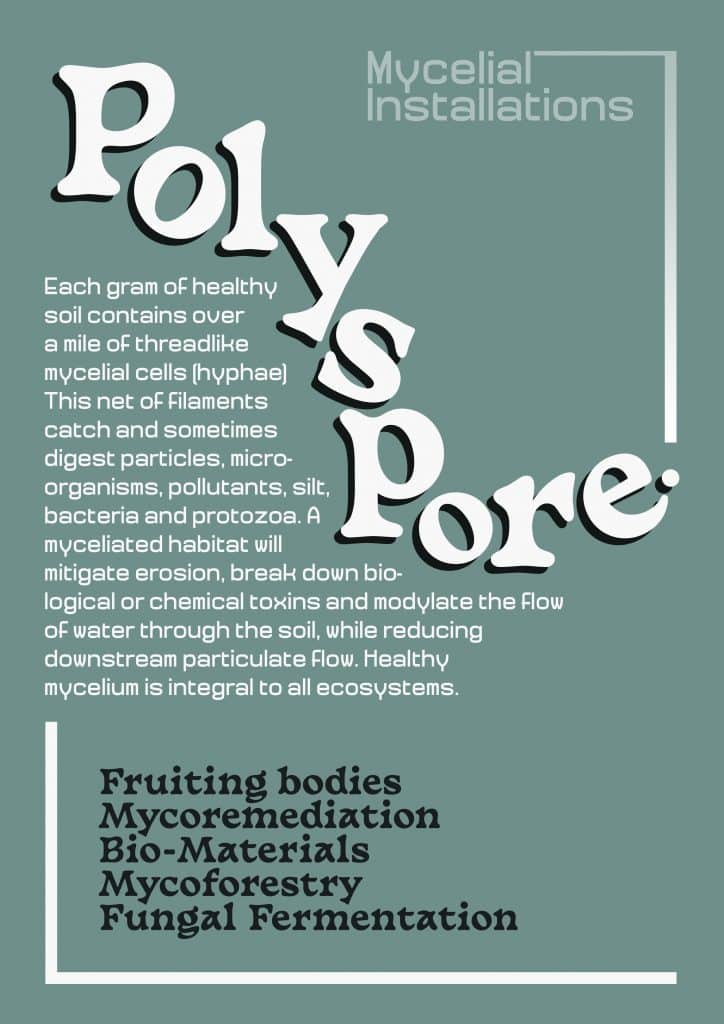

Dylan, while showing me the range of liquid cultures they have stored, explains the masses of things that mushrooms and mycelium can be grown for: “mycelium can be used to make packaging, furniture, leather, clothing – it can be moulded into anything. You can even make compostable turntable isolators!” He picks up a liquid culture of turkey tail, a fairly common mushroom found throughout the Northern Hemisphere. “There’s evidence that turkey tail is useful in fighting cancer.”

I ask him about lion’s mane, which I’ve heard is good for boosting cognition. “Yeah,” he replies, “lion’s mane extracts have been shown to fight plaque on the axons of nerves in the brain and body, and these are like the biological markers of dementia.” Amazed, I ask him if they have any of the extract. “Oh yeah,” he says, “there’s some in your coffee.” I look down at the mug in my hand and take a big gulp. I’ve been spiked with mushrooms before, but never lion’s mane.

Meanwhile, Mike is filling a huge gorilla bucket with substrate – a mix of sawdust and soybeans that’ll help form the bulk of mycelium’s food source. Eventually, when grain spawn is added (liquid culture grown on sterilised millet), it will provide the biomass that mycelium can grow through. This blend is placed into biodegradable bags, and the mushrooms fruit out of the side.

I help Mike mix the substrate, and then place it into a machine for pasteurization. There’s a Blue Peter moment, and Mike produces some bags of substrate that’re already pasteurized. We open them up, mix them with an inoculated grain (grain that’s been exposed to mycelium spawn), and reseal them. I write the date on them and then my name. “You can keep that one,” he says. I grinned at him the sort of smile that you see on Christmas. It was ripe with anticipation, happiness and appreciation in equal parts. There aren’t many gifts as unique and interesting as the capacity to grow mushrooms, and Polyspore has the capacity to give it to the world.

A couple of weeks later we visited Polyspore’s Altrincham studio on Friday evening. At about 5:40pm, a woman approaches the room where we’re talking and eating (Dylan, who once worked as a chef, shredded a bunch of oyster mushrooms with his hands, lightly fried them until they browned, added cumin, garlic, soy and some other umami-boosters. The result had the texture and taste of shawarma).

The woman’s head pokes around the open door. “I’ve just dropped my kid off at kickboxing outside. Can I buy some mushrooms?”

Mike puts his beer down and runs off to the grow room. “How about this?”

He hands the woman a block of grey oyster mushrooms, still attached to the biodegradable grow bag full of substrate. They’re the perfect age for harvesting, with downturned edges and little to no damage to the gills. She holds it in both hands. Mike holds the substrate bag and the woman, a hand on either side of the mushroom, gives it a gentle twist. If life was a cartoon it would’ve made a POP! sound as it leapt into her hands. She looked at it with wide eyes. They were full of desire. “What else you got?”

Mike runs off again into the grow room and returns with a king oyster that’s grown in a spiral. Whereas oyster mushrooms grow in a bracket on rows, a king oyster is huge and phallic. This particular specimen had grown around itself, like the curved and stubby tail of a pug. “It’s a bit… weird” confesses Mike. The woman is equally enthused. “I’ll take it.”

Mike weighs them both – just over 600g – and the woman is chuffed. She agrees to pay later – mushrooms on tick – and leaves happy.

There’s just something about them, we all reason. But they aren’t just enigmatic and exciting. On Polyspore’s website, the bio asserts that while they’re farming mushrooms, there’s the prospect that “fungus are farming us.” In essence, mycelium is convincing us to care for it and cultivate it. But the truth is darker than that: mycelium was here on earth when life was in its infancy, and it’ll be here when all living things are merely biomass, too. That’s the thing about mycelium: first in, last out.

On the table in front of us is the book Mycelium Running, by Paul Stamets. In mushroom circles, Stamets is a God, and his signature hat – made by Transylvanian artisans from a spongey mushroom derivative called Amadou – is a crown. If there’s a mushroom-related idea, Stamets has written about it. In 2005’s Mycelium Running, Stamets writes extensively about the capacity of mushrooms to clean up soil and rid land from various forms of pollution. “That’s mycoremediation. That’s what we’d like to explore,” says Dylan. “Mycelium can even clean up oil spills and convert them into functioning habitats in a matter of months.”

In 2007’s COSCO-Busan oil spill, mushrooms were deployed to remove some of the 58,000 gallons of oil from San Francisco’s Bay and at other ongoing spills from Chevron’s petroleum wells in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Mushrooms are so adaptive that they’ve developed ways to decompose waste matter as stubborn as oil.

The Polyspore boys are absorbing all the information they can around mycoremediation, with the intention of rolling out various local projects in and around Manchester. One such place is Highfield Country Park, a 70-acre area of open land on the east side of Levenshulme. Despite its charming name, the park has been used since the 70s to extract clay for the building industry, as a landfill site, the grounds of a cattle tripe factory, and for various dye and bleach businesses. The land sits pretty high up the degradation scale.

The basis of the mycoremediation project is the installation of mycelial mats into toxic or polluted land. Large volumes of spawn are implanted into the land in a singular mass and mycelial waves spread outward from the centre. Mycelium will digest bacteria, micro-organisms and pollutants, essentially mitigating erosion, removing biological and chemical toxins, and facilitating an easier movement of nutrients and water through the soil. “Healthy mycelium is integral to healthy habitats,” types Dylan, a couple of weeks after our first meeting. “We must work with our fungal allies to increase biodiversity and put an end to the devolution and loss of species brought about by so many of our modern practices; namely the use of pesticides, fungicides, plastics and other chemical toxins that harm and often destroy fungal networks.”

There are various admin loops the duo has to jump through, including approval from local ecologists and the council, but they hope it will be a pioneering project and potentially a UK-first.

It isn’t just the future that mushrooms have the capacity to shape. There are suggestions that without mushrooms and mycelium, humans wouldn’t be here at all. In a fundamental sense, mycelium has literally saved the planet on numerous occasions. In Stephen Harding’s book Animate Earth, he writes about the first trees appearing on earth, some 385 million years ago. That was the first time a new, novel substance had been introduced into the biosphere: wood. When wood grows, it extracts carbon from the air, and it accumulates in the woody bodies of dead trees. Importantly, it’s hardy stuff, and nothing on the planet knew a way to digest it or break it down. Much of this dead wood converted into the coal that we burn today, but if it had continued to pile up, so much carbon would’ve been extracted from the atmosphere and stored in the dead trees that the sheer amount of oxygen in the air would’ve turned the atmosphere into a precarious fireball-to-be. Fortunately, after 80 million years of evolutionary toil, decomposer fungi invented the capacity to digest the thick, woody tissue and absorbed the huge varieties of nutrients stuck in the wood. Without their digestive capacities, the planet could’ve frozen to death or been sparked, like the tip of a match, into a giant, all-consuming fireball.

In a more intimate and human way, mycelium and its fruit have facilitated the expansion of humanity across the globe. In 1991, two German tourists walking in the Austrian Ötztal Alps discovered a naturally mummified body preserved in the ice. Estimates put the life of the man somewhere between 3359 BC and 3105 BC, making him Europe’s oldest natural mummy. He – Ötzi, as he is commonly known – offers an unparalleled view into the life of a Copper Age European.

The circumstances of Ötzi’s death are unclear. He had various wounds from arrows and knives and traces of blood from at least four other people on his clothes. Ötzi most likely died fighting. One thing was for certain though: Ötzi was well equipped to travel. In the pockets of his leather clothes (some of which was bear leather, his shoes partly dear leather, his leggings goat) were two mushrooms: a birch polypore and a horse hoof mushroom.

Birch polypore is nature’s plaster. If you take a knife and carve a plaster-shaped strip from the underlayer, you can wrap it around a finger or stick it over a wound. It exhibits various antiseptic properties. It was, for all intents and purposes, Ötzi’s medkit. The horse hoof fungus is different. When dried, fluffed slightly and exposed to sparks, it will catch alight and smoulder for hours, essentially granting the ability to move fire from campsite to campsite with considerable ease.

“Horse hoof,” explains Dylan, “could’ve facilitated the movement of humans from North Africa into the colder parts of Europe.” The presence of it in Ötzi’s pocket suggests it was an essential piece of equipment for anyone in Europe at that time, and there’s textual evidence that Roman armies used to travel long distances by stringing together a long line of smouldering pieces, like lighting a cigarette directly off another when there’s not a lighter around.

It gets wilder: there’s a whole school of thought that suggests that early hominids, or proto-humans, might’ve consumed mushrooms with psychedelic properties alongside their normal diet, leading to various advances in consciousness. Terence McKenna propagated an idea in his 1992 book, Food of the Gods, where low doses of psilocybin – the active psychedelic compound in mushrooms – improve visual acuity, cognition and concentration. This is in extremely low doses – way before anything psychedelic happens. Microdosing of psilocybin has been shown to be effective at boosting mood, helping fight anxiety and inducing creative thoughts, all of which are traits highly valued for societal cohesion.

And then, of course, there are high doses of psilocybin. Groupthink, visions and abstract thought all sound like precursors to religious experience. McKenna would argue that psilocybin mushrooms were an evolutionary catalyst from which language, the arts, religion, imagination and human culture sprang. In this sense, mycelium, its fruit, and the compounds contained within it didn’t just facilitate the expansion of humans geographically, but spiritually.

I left Polyspore’s studio the first day holding the 2k bag of substrate inoculated with watercolour mushroom mycelium. I held it like it was a baby. “You look so happy!” Mike remarked. He was right – a smile beamed across my face. “I’m gonna look after it like it’s my own child.” I set off with substrate in hand, eager and ready to grow my own oyster mushrooms.

Later that evening I met my girlfriend at Manchester’s Central Library. Full of gusto and enthusiasm, I crept up behind her desk and slammed the 2kg bag of the inoculated substrate onto the wooden table, the dull thud echoing through the domed chamber. “Babe,” I shouted – forgetting my whereabouts – “you’ll never guess what this is!” I explained the symbolic importance of the bag of mushrooms-to-be and stared longingly at it. “Like it’s my own child,” I murmured, and explained the sort of patriarchal love that I felt for it; how I couldn’t wait to see the mushrooms grow, how I’d watch them and care for them.

I thought about the line I’d read on Polyspore’s website. “We aren’t farming them,” it read. “They’re farming us.”

I stared at the bag one more time, pondered its future, and realised that mycelium, just like cats, has made itself so interesting that we – Polyspore with their elaborate studio, me with my desire for its fruit – have decided to go to extreme lengths to keep it around. Cats, like mushrooms, are interesting. They’re elegant and simultaneously stupid. They hunt pests and make great content for memes. What do mushrooms do? Well, they might just save the world. And they taste bloody good.