Some artists and brands make more money dead than alive. But if something is dead, who’s behind their collaborations, and why?

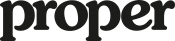

A few days ago, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s NY apartment went onto the housing market. The Great Jones Street building, where Basquiat famously lived, was rented to him by his fellow artist and mentor, Andy Warhol, who found a young and homeless Basquiat writing graffiti on the outside of buildings in 80s Lower Manhattan. Warhol took Basquiat under his wing, gave him guidance, a small fraction of stability, and catalysed Basquiat’s growth from street artist to one of the most successful artists of the modern world. For reference, in 2017, 29 years after his untimely death in 1988, Basquiat’s 1982 painting, Untitled, sold for $110.5 million USD at Sotheby’s, setting records as the highest price paid at an auction for any artwork created after 1980, and therefore making it one of the most expensive paintings ever sold. Not bad for a kid who once declared that he thought he was going “to be a bum for the rest of [his] life.”

Shortly after his overdose in the apartment, corporate renters removed the extensive graffiti from the outside, and the building housed a Japanese restaurant until very recently. Basquiat’s legacy is preserved through a plaque that reads “Basquiat’s paintings and other work challenged established notions of high and low art, race and class, while forging a visionary language that defied characterization,” and the haunt generally serves as a pilgrimage site for art lovers and graffiti writers.

The entire 57 Great Jones Street building is on the market for $60,000 USD per month, including taxes, according to The Daily Beast, who contacted the NY Meridian Capital Group.

Interest in Basquiat’s work has sky-rocketed, which runs analogous to a new-found art world ‘interest’ in Black artists – an irony which would not be lost on Basquiat, given his work is entirely motivated by anti-colonialism, class-struggle and black experience, and frequently spoke out against being labelled as a ‘black artist’ and not an ‘artist’, the former a category which served to undermine and separate Basquiat from the art world he lived in, performatively reinforcing the experience of being an outsider.

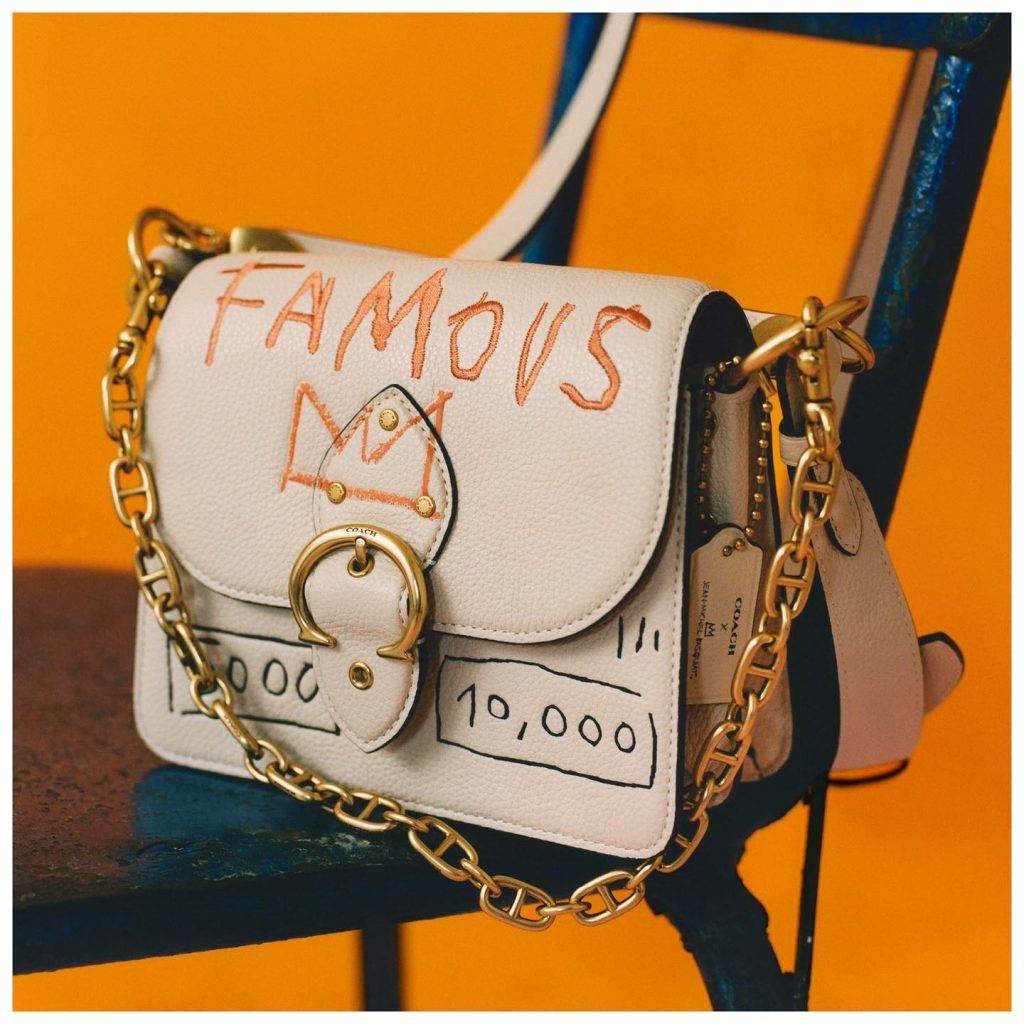

Since Basquiat’s death, his estate, controlled by his two sisters, has built a licensing empire that consists of frequent collaborations with brands like Dr. Martens and Yves Saint Laurent, products including branded barbies, Coach bags, and collaborations with high street brands like Zara.

Basquiat’s estate works with Artestar, a creative agency that licenses Basquiat’s imagery. The agency is also responsible for the omnipresent proliferation of Keith Haring imagery, where, similarly, his iconography and figures have entered into a perpetual collaboration with the fashion world, including a world first Pandora collaboration, Drake’s OVO label, numerous Uniqlo collaborations, and, rather unfortunately (!), a Primark collaboration. Oh yeah, and these are just in 2022.

Officially, Artestar intends to introduce Basquiat’s work to the wider world and younger generations. Linda Basquiat told Artnet earlier this year that “if a person can’t afford to purchase a painting, they can still purchase something, some physical thing that gives them the ability to have access to Jean-Michel’s artwork,” which acts on the economic assumption that in order to access Basquiat’s work you have to purchase something produced by the anti-capitalist artist. Artestar also have the cheek to highlight Basquiat’s brand profile with a quote of his: “I think I make art for myself, but ultimately I think I make it for the world,” as if to justify the relentless and frequent collaborations.

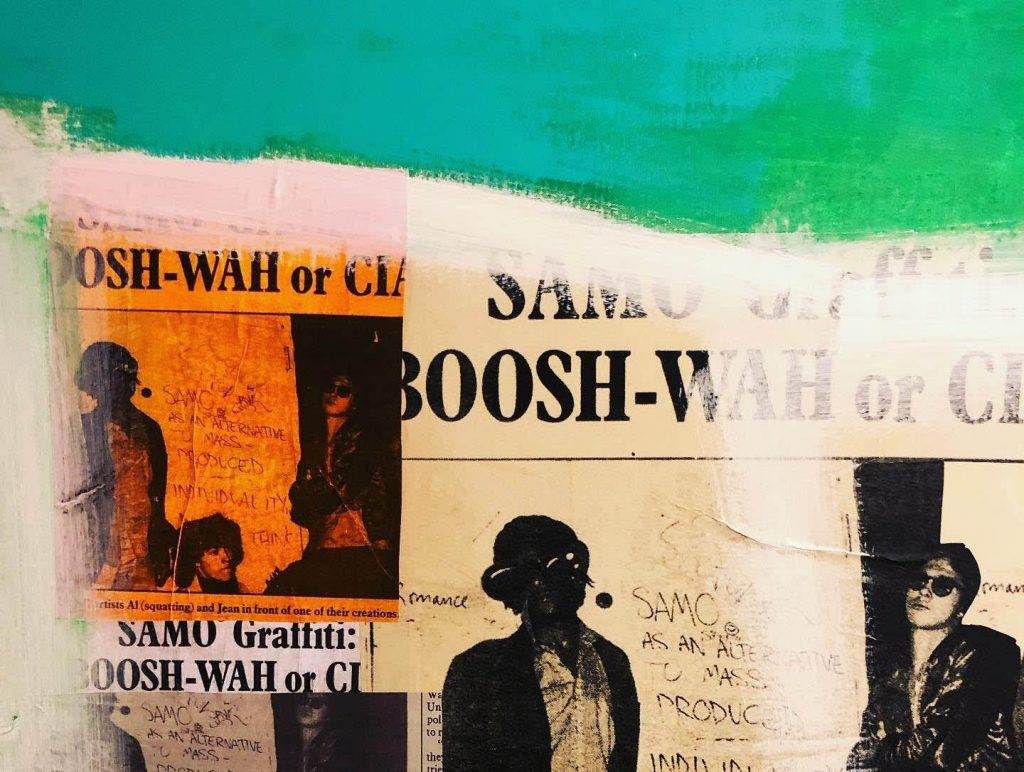

Several of Basquiat’s close friends and fellow artists have spoken out against the work of the family-owned estate, with Al Diaz, one half of SAMO, Basquiat and Diaz’s teenage project, astutely recognising that the people who buy Basquiat’s art are the people he was targeting. They are the oppressors – and this is a charge that could equally be aimed at the Basquiat Estate in itself. Alexis Adler, a roommate and close friend of Basquiat asserts to The Daily Beast that “the commercialization and commodification of Jean and his art at this point — it’s really not what Jean was about.”

The issue at hand is not isolated, and is certainly not just an issue for artists. Over on our shores, and closer to home still, The – beloved – Hacienda makes more money now than it ever did when it was open. Of course, when it opened, it cost Tony Wilson and Peter Hook an estimated £10 mil of their own money, and they reckon that every guest who went through the doors cost them a tenner. With that in mind, it wasn’t exactly a money pit at the time. Now, however – and not dissimilar to the goal of Linda Basquiat – The Hacienda is granted immortality through collaborations, brand licensing deals and revival club nights.

Recently, The Hacienda was teamed up with Bioworld via Talisman (the former a clothing license distributor, the latter a brand expansion consultancy firm) that resulted in Boohoo x The Hacienda. There are better ways of commemorating the pioneering legacy of – not just The Hacienda but of Tony Wilson – than with Boohoo, and Peter Hook, who is now in charge of licensing the club night following Wilson’s death, ought to know better.

The only redemptive factor is that Boohoo UK is based in Manchester, which sort of makes sense. (That’s also the only redemptive factor for this gin collaboration, too.) The fear is that the collaboration will start a slippery slope which eventually ends in the same sort of image degradation that happened to the Ramones x Primark tee. And not to mention that the ethos of the original Hacienda is so far removed from that of Boohoo. Manchester is a city with a thriving fashion scene. There are much better candidates out there, and that’s if and only if collaborations with clothing brands are even necessary. By all accounts, the Boohoo collaboration is lazy and thoughtless, and acts as a disservice to a once-great brand.

In many cases, people and brands are worth a lot more dead than alive. For some reason, a legacy makes a more compelling collaboration than a living, breathing entity. It’s a silly world, isn’t it, where there’s no limit to the extent you can dig up the dead for their image, just to pump out the same old shit and the same old reproductions. There was an artist who commented on this way back in the late 70s. He and a friend used to write SAMO on the walls of New York. SAMO, pronounced Same-Oh, short for the same old shit, time and time again. What was his name? Basquiat.