An absolutely irrefutable and legitimate case for why Die Hard is a Christmas film, including parables, character development and music.

It’s one of those debates that pops up every year and runs analogous to heated conversations about when it’s okay to listen to Christmas music, when it’s right to put the tree up, and how long you should suffer in silence at the dinner table in the face of unwarranted politics.

Someone, at some point, is going to make the case that Die Hard is or isn’t a Christmas movie, with both sides just as impassioned as the others. We’re here to tell you that it is undeniably a Christmas film, and if you argue that it isn’t because the holiday element only plays a minimal role in the actual plot of the movie (which is a falsehood anyway), then neither is Home Alone.

It makes sense to start the discussion with a simple question: “What makes a Christmas movie?”

Besides being set around Christmas, every Christmas movie contains a parable or a message about the things that Christmas makes us value. In Dickens’ A Christmas Carol – perhaps the most widely known Christmas story of them all – the meaning is to forgo greed and monetary wealth in favour of family and friends. Die Hard perfectly embodies this notion, as the thieving, money-obsessed terrorists are rightfully thwarted in their attempts to steal money from the hard-working corporation, and this provides the perfect backdrop for Bruce Willis AKA John McClane to rekindle the love with his estranged wife. The conclusion is obvious: we’re dealing with a Christmas film of Dickensian proportions. Except there’s guns and explosions.

Die Hard takes place on Christmas Eve because the Nakatomi Corporation’s office party takes place on Christmas Eve (imagine that). McClane’s distant wife, Holly, (yes, Holly!) invites the detective to the party, where her colleagues celebrate the Christmas spirit and their capitalist employer’s generosity by sniffing coke in the office and desperately flirting with each other. McClane’s arrival brings the sort of unwelcome glares you’d imagine from finding a fed watching you rack up, and Willis’ face, post-argument with wife, shifts into an unpleasant, miserable, what am I doing here stare that makes him the perfect medium for a festive renewal.

German terrorists arrive with immediate effect and everyone, except our man McClane, is taken hostage. It’s blatantly obvious that our terrorist troop is a metaphor of the same ilk as the Grinch. Pre-Snape Alan Rickman plays an anti-Claus, and his gang of nihilistic German elves know that the best time to pig into the fat underbelly of a corporation – AKA $640 million in untraceable bearer bonds – is when they’re at their most joyous and therefore vulnerable. Die Hard flips the switch on the usual Christmas caper by accepting that the long-haired, Aryan antagonists are beyond redemption. Unlike the Grinch’s, their attempts to ruin Christmas will not go unpunished, and there’s only one man for the job. This man, whose face was defeated and glazed over, now shines as the Christmassy harbinger of (deserved) death.

There are, of course, numerous Christmas references throughout the film. Frank Sinatra’s Let it Snow plays the film out, and Run DMC’s Christmas in Hollis sets the tone early on during the build-up to the Christmas party, after McClane explicitly asks his limousine driver for Christmas music.

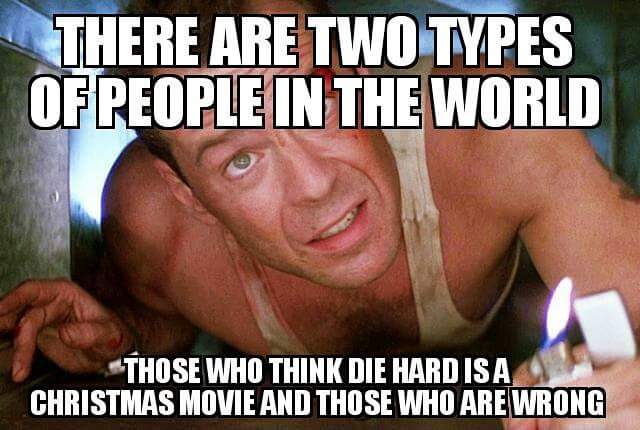

Of the most tasteful Christmas references, however, none can compare to McClane’s sending of a poorly trained terrorist down an elevator. Said terrorist is strapped to a chair and wearing a Santa hat, before anti-Claus finds him. The victim’s grey sweatshirt reads: NOW I HAVE A MACHINE GUN. HO HO HO, which Rickman reads out with a tone so disgusted and full of dread that the entire meaning of Christmas is conjured and discredited with three distinct syllables. It’s a sentence executed so well that Rickman accidentally laid the foundations for a lifetime of tragic villain typecasting.

Ultimately, Die Hard is the story of an emasculated man who is so scared of spending Christmas alone that he agrees to spend Christmas Eve at an office party with a wife he hasn’t spoken to in years. Through a combination of violence and tough love, he discovers that Christmas is a period for redemption and change – if, of course, you’re on the good side of the gun – and his love blooms once again.

While it’s easy for us to make this case (because it’s true), Willis himself argued against the idea in his 2018 Comedy Central Roast, while screenwriter Steven E de Souza makes a compelling case that it is. Whatever the central characters in the film’s creation think, one thing is for certain: we live in a world that constantly updates and redefines itself. The very existence of debates arguing that Die Hard is a Christmas film solidifies its Christmassyness, and the two themes are now inseparable.

If in doubt, follow the data, where Stephen Follows rightly concludes: “It may or may not have been, but it most certainly is now.”