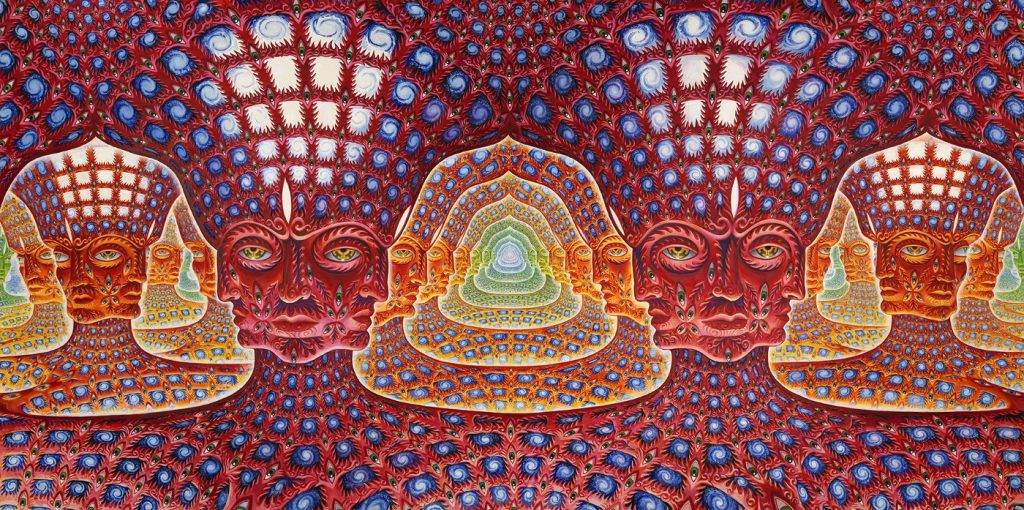

Seeing as we’re deep into Liberty Cap season, it feels prevalent to look at mankind’s relationship to psychedelics, and see how mushrooms are permeating the worlds of fashion and iconography.

The first time SWIM – head to The Shroomery or Erowid for that abbreviation – took a variation of magic mushrooms, they were 14 and they’d ordered them online. They were shipped in discreet packaging, the only tell-tale sign that the parcel contained anything illicit being the sender’s address: Amsterdam. This was back in the 2000s when you could order psilocybin-containing truffles from Holland, following the Dutch authority’s ban on actual magic mushrooms in 2007. Truffles aren’t technically mushrooms, they’re sclerotia, a sort of underground analogue to the mushroom’s aboveground body. Like with all drug policies, if you ban one thing, an alternative appears. With the Dutch mushroom ban, producers needn’t look very far – they simply had to dig a bit deeper.

Several years after that, SWIM alarmed their mother by asking for three books for their 16th birthday: Terence Mckenna’s Food of the Gods, John Lily’s The Centre of the Cyclone, and The Electric Koolaid Acid Test, that chronologed the journey of Ken Kesey and his merry gang of psychedelic Beat pranksters.

All of these books have one thing in common: they place psychedelics at the forefront of a consciousness revolution, one that has been raging since the 60s. What they all fail to do, however, is actualise one. While the hippies had acid and flower power, the second psychedelic revival of the 80s had crossbred mushroom strains and The Esalen Institute, the 2020s has fashion, untapped graphic design distribution, and decades of grey area laboratory research to stand on. There’s something about the current commercial world’s fascination with mushrooms and psychedelics that feels like something more than trends moving cyclically. It feels like we’re on the periphery of a bursting bubble – although, in a way, everyone that’s ever joined a movement feels that way.

Psychedelics, and therefore magic mushrooms, have never been more popular. Mushrooms, from the obvious red and white amanita muscaria lined children’s Christmas books – I’m certain The Night Before Christmas pop-up book that I read as a child features mushroom imagery – to the browner, less immediately engaging varieties, are everywhere. Stussy’s SS20 collection featured heavily on mushroom imagery, as did Fiorucci, Gucci, and Marc Jacobs. And that was all in 2020.

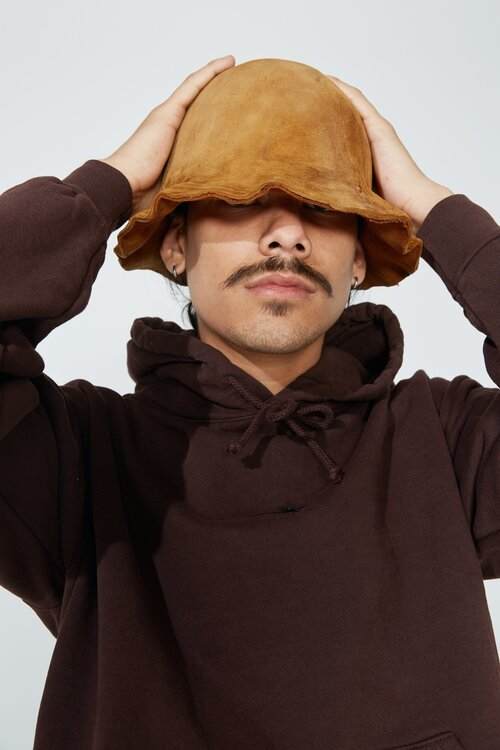

These ephemeral toe dips into mushroom motifs are important, because while they’re merely trends, someone like Gucci wouldn’t take a risk unless there was a degree of longevity in it. Several other brands have built their entire portfolio around it: Eden Power Corp’s SS21 was shot entirely in a mushroom lab, and featured an Amadou hat made from tinder mushrooms in the style of Paul Stamets. Story mfg has been recycling patchwork and embroidered mushrooms on everything from dresses to fleeces and sweaters and hats since they started in 2013. Google ‘mushroom’ and ‘fashion’, and there’s no end of blogs and articles all hailing mushrooms as the season’s hottest trend, from interior design to make-up, and from high fashion to drug choice.

Melvin Sheldrake, the author of Entangled Life, a landmark text in contextualising the importance of mushrooms in uniting the ecological world, explains to Slate that part of the new-found interest in fungi lies in their psychedelic properties: “I think the remarkable effect of this fungal compound on our human minds has opened many people to the fungal world.” There are countless studies detailing the efficacy of mushrooms in treating everything from PTSD, depression and migraines to addiction. We’ve reached a point where the evidence is irrefutable. To turn a blind eye – as many politicians are still apt to do – is as idiotic as climate change denial.

Something, somewhere, has not just put the humble mushroom on the tips of everyone’s tongues, but made it fashionable, too. The humble mushroom that might’ve, if you’re open to a wee bit of scientific conjecture, might’ve travelled to the earth on a frozen asteroid and catalysed the development of life as we know it.

The reason for the mushroom’s cultural omnipresence might be summarised as follows: mycelium, the body that mushrooms fruit from, and therefore all their varieties and iterations, is one of the most useful biological materials on earth. There are literally no limits to what a creative mind can do with mycelium. In Proper Mag 39, Polyspore ruminate over the possibilities, from cleaning the brain’s synapses with Lion’s Mane, to compostable turntable isolators made from mycelial root.

This morning, I returned from a trip to Kinder Scout with three distinct mushrooms with three distinct uses: a couple young Puffball mushrooms that are delicious when fried, a small Tesco bag full of Liberty Caps, and a large selection of Shaggy Inkcaps, which you can store in a tupperware and use to create ink. In 1780, Danish biologist Otto Friedrich Müller described how they were used by monks as a source of temple ink.

In the modern day, this resource prevalence has put the mushroom everywhere, from Silicon Valley’s interest in microdosing, to Stella McCartney and eco-tech-fashion’s interest in mushroom leathers as an alternative to animal leather. Add our post-covid appreciation for just going outdoors, gorpcore, and the shared need to post a picture of a mushroom on our Instagram image dumps, and everything begins to make sense. Mycelium is a labyrinth of thin tubes that grows underground, connecting the domains of soil, trees, algae, plants and animals. As an extension of the living entity’s lust for life, mycelium has now permeated the culture of fashion, and not-so-subtly embedded itself in all of our minds through the world of social media, image sharing and iconography.